In the Gulf of America at the easternmost tip of Louisiana, sits the historic Chandeleur Islands, a thin chain of barrier islands formed over 2,000 years ago. The Islands were given their name by French explorer Pierre le Moyne d’Iberville who came upon them while searching for the mouth of the Mississippi River along the Gulf Coast. His party landed on the Islands on February 1, 1700, the eve of the Christian feast day known as Fête de la Chandeleur, inspiring his naming choice.

The Chandeleur and Breton Islands make up the Breton National Wildlife Refuge, the second-oldest National Wildlife Refuge in the country, established on October 4, 1904, through an executive order by President Theodore Roosevelt. An avid outdoorsman, Roosevelt saw the need to protect the islands as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds. During his presidency, Roosevelt established the first 55 federal bird reservations and game preserves across the United States, protecting habitats for countless species.

After his time in office, Roosevelt traveled to the Breton National Wildlife Refuge in June 1915, marking his only visit to a refuge he had established. While visiting the Refuge, Roosevelt wrote: “I was very glad to have seen this bird refuge. With care and protection the birds will increase and grow tamer and tamer, until it will be possible for anyone to make trips among these reserves and refuges, and to see as much as we saw, at even closer quarters. No sight more beautiful and more interesting could be imagined.”

President Theodore Roosevelt Visits the Breton National Wildlife Refuge in June 1915.

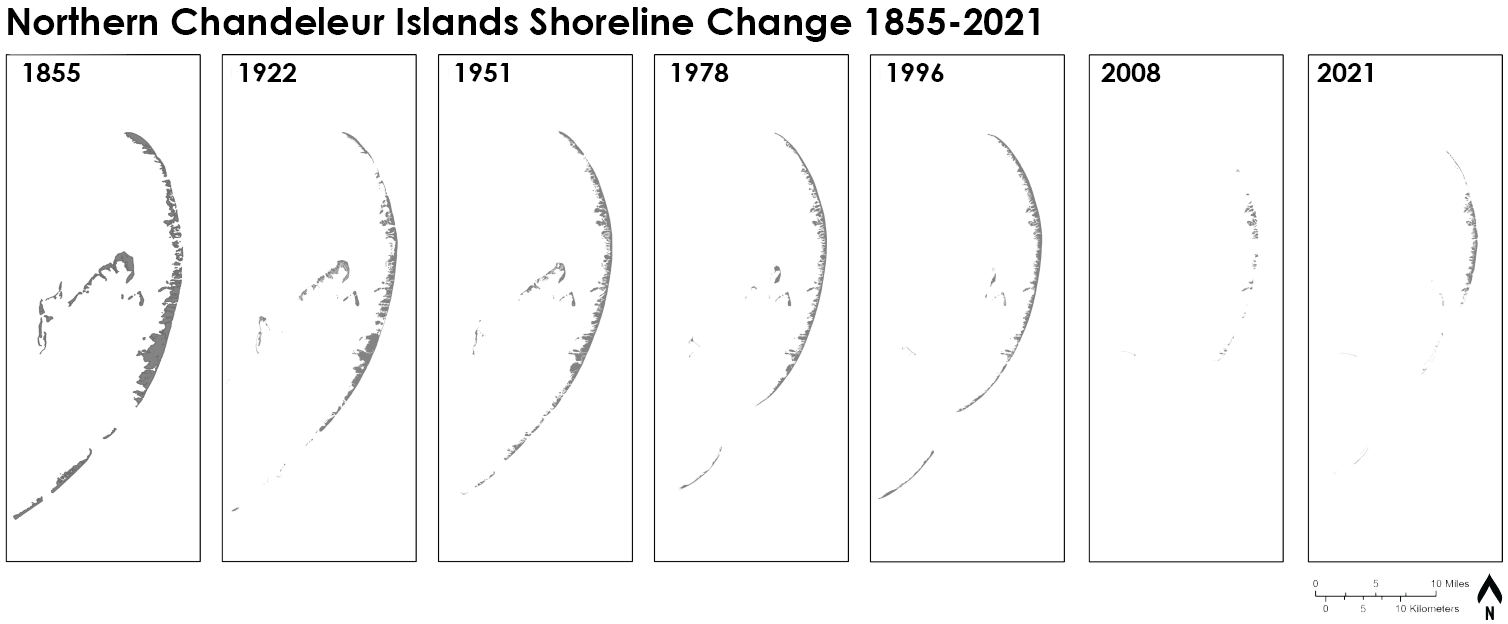

Since Roosevelt’s visit, the barrier island chain has changed drastically. It is estimated that the Wildlife Refuge spanned 11,000 acres in the late 1800s. Today, the refuge covers less than 1,000 acres.

Graphic provided by The Water Institute.

The islands have lost nearly 90% of their landmass over the past 200 years due to intense weather events, including Hurricanes Georges (1998) and Katrina (2005). The islands were also heavily oiled during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, impacting many birds, plants, seagrasses, and aquatic species that inhabited them.

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Impacts on Chandeleur Islands. (Photos Courtesy of USFWS)

What’s At Stake

The islands are home to world-renowned recreational fishing and bird watching and serve as an important storm surge barrier and first line of defense for some of southeast Louisiana’s most densely populated areas. The island chain also plays an important role for various species, providing nesting grounds in the spring and winter foraging habitat for migratory wildlife. Seven federally designated Species of Global Importance, including the Piping Plover, Red Knot, Reddish Egret, Snowy Plover, Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle, Loggerhead Sea Turtle, and Gulf Sturgeon, can be found on the islands.

Birds

World-renowned ornithologists have visited the Chandeleur Islands to conduct surveys on the more than 200,000 birds, including piping plovers, red knots, redhead ducks, and other birds, that inhabit the islands in a typical year. More than 170 species of birds have been documented on the island in a single year.

Doppler Radar picked up Roost Rings over the Chandeleur Islands when approximately 300,000 birds took flight at Sunrise. (Video Courtesy of Steve Caparotta, WAFB)

The islands play host to secretive marsh birds, passerines, pelagic birds, colonial nesting birds, waterfowl, wintering migratory birds, solitary nesting birds, and more from across the globe. Banded birds that visit the Chandeleur Islands have been observed in at least 33 other countries around the world, which is why the National Audubon Society has deemed them a “Globally Significant” Bird Area.

An extremely rare observance of a Chandeleur Gull egg hatching, or “pipping,” was recently captured by scientists on South Chandeleur Island.(Video courtesy of USFWS)

The Chandeleur Island chain is notably the only nesting ground in the world for the Chandeleur Gull, a hybrid of the Kelp Gull and the Herring Gull. This species was first observed in 1994 by Charlotte Seidenberg. Subsequent visits revealed a potential breeding population of these hybrids.

There were once around 100 Chandeleur Gulls who laid claim to the islands, but the numbers have decreased to only 24 adults and four chicks as of 2023. Without a concerted restoration plan, the nesting ground of the Chandeleur Gulls will continue to disappear, and the species could be lost.

Sea Turtles

Despite the belief that the Chandeleur Islands were unsuitable for nesting sea turtles, CPRA and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) have documented 136 sea turtle crawls over the last three nesting seasons by three species of sea turtles — Green Sea Turtles, Loggerhead Sea Turtles, and Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtles.

Trail camera footage of sea turtle hatchlings on the Chandeleur Islands in August 2024.

Kemps ridely sea turtle hatchlings have been observed crawling to the Gulf in 2023 and 2024. This observation marked the first time in over 75 years that hatchlings of this endangered species has been observed emerging from the sand on Chandeleur Island. Surveys conducted in 2024 marked the third year in a row that successful sea turtle nesting has occurred on the Chandeleurs and surveys are already underway in 2025.

The islands are now documented as having the second-highest crawl density beach in the northern Gulf of America. Read more.

Fisheries, Seagrass, and Other Wildlife

The leeward side of the Chandeleur Islands is home to the most expansive seagrass beds in the northern Gulf of America, collectively spanning approximately 5,200 acres. Species observed in these seagrass beds include Shoal Grass, Star Grass, Widgeon Grass, Manatee Grass, and Turtle Grass. This is the largest, most botanically diverse assemblage of seagrasses in the northern Gulf of America. Many marine species, including mammals, benefit from the abundant and diverse collection of seagrasses.

Dolphins are observed in the sea grass meadows of North Chandeleur Island.

These seagrasses provide habitat for a diverse assemblage of invertebrates and fish that attract a large number of dolphins throughout the year. Dolphins from both the Mississippi River Delta and the Mississippi Breton Sound Estuary Stocks utilize the Chandeleur Islands and their seagrass meadows.

Over the course of a year, CPRA spotted 255 dolphins along the islands. Dolphin observations are 2.5 times more likely near the Chandeleur Islands than in the marshes of St. Bernard or the Chandeleur Sound, highlighting dolphins’ attraction to the habitat provided by the island chain. The dolphins found along the islands also benefit the breeding stocks of dolphins from Mississippi and Louisiana, bolstering their population numbers.

The sea grasses serve as forage for herbivorous aquatic organisms such as sea turtles and the occasional manatee that wanders into the area. Their root systems help to preserve the seafloor around the island by anchoring vital sediments in place. They also provide shelter and essential nursery habitat for juvenile fish and shrimp.

The Chandeleur Islands are also an integral part of the Gulf of America’s abundant fish and shellfish resources. The island provides aquatic habitat and nursery grounds for near-threatened, threatened, and/or endangered species such as Lemon Sharks and Gulf Sturgeon. The area is the only nursery ground for lemon sharks in the Northern Gulf of America. Dr. Michael Dance, an Assistant Professor with the Louisiana State University College of the Coast and Environment, observed that the islands also support Gulf sturgeon from the Pearl River, Pascagoula, and Mobile River breeding stocks.

Other noteworthy finfish species that inhabit the immediate area around the island are the Tarpon, the Spotted Seatrout, and various species of snapper.

A Smalltooth Sawfish, an endangered species, utilizes the waters around the Chandeleur Islands. (Photo Courtesy of Captain Kyle Johnson)

Restoration Plan

CPRA is currently in the engineering and design phase of the Chandeleur Island Restoration Project, which will restore 13 miles of the barrier island chain. Once complete, the restoration will increase the overall, long-term resiliency and sustainability of these landmasses.

Included in the 2023 Coastal Master Plan and the Louisiana Wildlife Action Plan, the Chandeleur Islands Restoration Project will provide significant protection to several coastal communities through a whole ecosystem restoration approach.

Project goals include:

- Restore and conserve bird nesting and foraging habitat.

- Enhance sea turtle hatchling productivity while restoring and conserving nesting beach habitat.

- Restore and enhance submerged aquatic vegetation (seagrasses).

- Create, restore, and enhance barrier islands.

Project development began with a robust data collection program designed to determine the existing conditions for topography, geotechnical properties, habitat classifications, wildlife abundance, and description of wildlife habitats. Through analysis of the collected data, restoration concept features were developed to determine which features would best assist in meeting the Project Goals.

These concept features are combined in various ways to develop Restoration Alternatives. The alternatives are then analyzed to determine which alternative best meets the Project Goals for the available construction funding. Once an alternative is selected the Project moves into the Preliminary Design, Permitting, and Final Design Phases. Construction for the Project has been targeted for early 2026. Once constructed, the restoration project will re-introduce eroded sand back to the island, restoring lost wildlife habitat and increasing the island life span by decades.